We’ve had the honor and pleasure of interviewing video game engineer and producer Paul Machacek, a thirty year veteran at Rare who has worked on a plethora of their games over the years such as Battletoads, It’s Mr. Pants, Banjo-Kazooie, Donkey Kong Land, and many, many more! Read on to learn about a completed Battletoads game you didn’t know about, the story behind the infamous Stop N Swop, why Battletoads is so hard, and how you could have a career as a video game engineer…

RareFanDaBase: Who was your biggest inspiration to want to pursue a career as a video game engineer?

Paul: “Ultimate Play the Game”! There were other games I liked, particularly prior to Ultimate coming on the scene, but once they got rocking and rolling there was nothing else to compare. Their gameplay was usually great, though could be very hard and unforgiving in places (getting killed by instantly spawning creatures as you go up/down between rooms on Sabre Wulf, pixel perfect jumps over spiky things in Knight Lore or falling half a dozen hard-fought rooms in Underwurlde). However, they looked like magical arcade games on lowly home computers and were just plain special. Sabre Wulf, Knight Lore (& Alien 8), Underwurlde and Nightshade heavily influenced me to the point that I wrote a 3D isometric game called Superhero that Codemasters published about the time I joined Rare in 1988.

RFDB: During the NES era, Rare released an incredible 47 games for the console. What was the driving force that pushed Rare to accomplish such a feat?

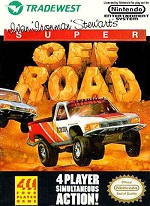

Paul: Money. It was a start-up studio that needed to establish itself and that took money. It was possible back then for 1 engineer, half an artist and 1 eighth of a musician to write a game from scratch in a few months that could sell a million copies. Even 100K copies brought in far more money than was spent. Our agent in Miami (Joel) kept doing deals over other people’s IP, either for us to port an arcade game (or something) to a Nintendo platform (eventually Gameboy was including in this frenzy as well), or to write an original title of our design for those IP’s. So Rare ended up doing US television show spinoffs such as Jeopardy and Wheel of Fortune, but also film or comic tie-ins (Beetlejuice, Spiderman), and the obligatory wrestling games around the WWE or WWF franchises. One of the engineers even became a master at doing Pinball machine conversions for NES. In amongst those, there were enough funds that allowed a few people to look at creating fully owned games with no external involvement/ownership at all, such as Sneaky Snakes and RC Pro-Am. When I started at Rare in July 1988, I was the 8th engineer in the studio. Once I got a game to work on (Super Off Road was my 1st for Rare) then there were 8 games in production at once, each taking between about 3-5 months to write. That’s why we could do so many so quickly. However, eventually, we needed to move on and build a more tangible franchise of our own, rather than just isolated titles, and that’s where Battletoads came from.

RFDB: Did you always have free reign when working on other people’s IP or was there any big restrictions of what you could or couldn’t do?

Paul: Personally speaking, we were mostly left to our own devices. We never had to sit in design meetings with IP holders or anything like that. Towards the end of projects, when the IP holders saw what was coming we’d get lists of “mods” faxed to us to “make your game better”, but honestly, coming into the office in the morning and finding a faxed instruction to “change that blue colour to red because it will sell more” was not much help. The most contentious problems I had were around Super Off Road actually. There were two issues. The minor one was that the “scorecard ladies” that were depicted appeared in bikinis (as they did on the arcade machine), however Nintendo was quite family-friendly and wanted us to “tone them down a bit”. That was a red rag to a bull for Kev Bayliss so every time such a request came in he just made them “more obvious”. Eventually the mid-tummy area was coloured in to be the same as the bikini which made it look like a one-piece swimsuit, but the ladies still became “less subtle” in the process.

The other problem was that someone at Tradewest (the publisher) decided it “didn’t look very good”. Actually, it looked f’ing awesome for a NES but we ended up in a long, hot, difficult meeting with the 2 young engineers involved in the franchise back at Tradewest. They had been responsible for the arcade machine and sat on one side of a table at Rare, and I sat the other side with Tim and Chris Stamper. After a couple of hours of not getting anywhere I changed tack and asked them to tell me a bit about the arcade hardware they had created the game on. Superficially, it was architecturally similar to the NES (character banks, character mapped screen, sprites etc), however the arcade board was significantly more powerful, way more colours, much larger screen buffer, way more characters, way more of everything in fact. So, I quietly nodded my head, and when they finished I told them this and ran through all the specs the NES had to offer to counter what they had just told me. They sat there with their jaws dropped, suitably impressed, and when I had finished they asked me “how on earth did you manage to get this onto a NES?” to which I responded “F’ing hard work”, and the meeting ended amicably there. Our NES game sold 1 million copies!

RFDB: Battletoads… how does it feel having worked on what is perceived as one of the most difficult video games ever made?

Paul:: We’ve just been through the 20th anniversary of Banjo Kazooie and lots of people are raving about how it made them feel as kids, and that gives you a nice feeling. Battletoads is the same, it keeps coming back and Microsoft just recently announced that there’s a new game coming for 2019. I wrote four Battletoad games in the early 1990’s, all for Gameboy, and it’s certainly cool that the franchise is still known a quarter of a century later and is often referenced for its difficulty. When the CEO of Groupon stepped down a while back he said something like “don’t underestimate how hard it is to run a start-up and grow it so quickly, it’s as hard as the Speederbike level on Battletoads”. If it can be a tiny bit of 20th century culture for a few people, then it can’t be bad to have spent time on it. As for the difficulty, well, I never tried to play a BT game all the way through. As I’d develop I’d boot the game directly into the level I was working on and obviously played it to death. Each time I completed a level (to ensure it worked) I’d then tweak something to make it harder, then I’d get a member of our test team to sit next to me and if they completed the level I’d make it a bit harder. So, we deliberately create individual levels that were designed to be “rock hard” on their own, let alone strung together into a sequence of nine that made up a game. Good luck everyone.

RFDB: What has been the most challenging and most rewarding game you’ve worked on?

Paul: That’s pretty hard to answer because several titles vie for rewarding and/or challenging, and they don’t necessarily coincide. I’m very proud of Superhero (published by Codemasters in 1988) because of what it meant to me at that time: it was the most technically challenging thing I’d done to date (by some margin), looked the most polished and professional, and got me my job at Rare when I showed it to the Stampers. I was relieved to get Super Off Road out of the way because I had now completed a game for Rare. Beetlejuice didn’t go so well, and that was mostly down to a lack of planning and communication with others about what we should be doing. However, then came WWF Superstars.

Long story short, Tim asked Kev Bayliss and me if we could pick up a title that someone else was doing that wasn’t going too well. I said I didn’t want to touch someone else’s code, especially given the circumstances, to which he agreed, and suggested it would just be a lot cleaner to start again and write it from scratch. It was our 1st Gameboy title, but the GB was architecturally not dissimilar to NES, and was Z80 based which was a processor I knew well from ZX Spectrum and Amstrad CPC days. Then, in that meeting, I asked Tim the fateful question “What’s the deadline”, to which he responded, without blinking, “Saturday”. Now, that really focusses your mind, but Tim followed up with “…if you could do it in 3 months I think we can stall the publisher long enough”. Three months and one week later our Test department signed off on the final build to go to manufacture. Win!

Loved doing the 1st Battletoad game on Gameboy as we could design a bunch of new levels to complement what had been done on NES, but Kev and I carried on the momentum from WWF. One of my prouder achievements was running the Donkey Kong Land team and getting that game onto the hardware which was a technical achievement. That lead into working on Dream v2.0 on N64 for 16 months, which was a problematic period that did not ultimately create a game, but it left a couple of foundations that we took forward in the subsequent 16 months and produced Banjo-Kazooie on which I did a huge amount of technical engineering work as well as setting up a lot of objects and puzzles in the game. The tech behind Stop’n Swap was my idea and I developed a demo to show it could work. Solving tech puzzles is fun, and the legacy of this (and what happened before we shipped the game) “kept fans entertained” for years afterwards. Sorry folks.

It’s Mr Pants dragged on in the background as an on/off part time thing for about 5 years unbelievably. It had gone through various iterations and jumped to more advanced Gameboy hardware. I had a huge influence on the humour and nonsense in that game, and worked very well with Ryan Stevenson, trying to make it as silly as possible. I’m generally well pleased with how it turned out, however it was supposed to have a multiplayer mode where every time you cleared a shape the blocks would be sent to your opponent’s Gameboy and would accelerate their snake forward, reducing their playing area. It got pulled right at the end for “silly reasons”.

Viva Piñata Pocket Paradise was something I loved working on. We had a great team who did some awesome tech work to get that onto the hardware. It genuinely looked fabulous and I want to give nods to Joe Humfrey and Lee Hutchinson for their contributions there. I got to spend a bit of time doing design work and laid out how the icon menus for tools and other things would work, and also the “continuous click-through” ability to dig through the encyclopaedia to understand what you needed to do. I’m so proud of how that one turned out, it looked and played absolutely fabulously, and got 2 BAFTA nominations as well.

Working with Kinect also provided a lot of diverse experiences that involved scanning people and loads of User Research of various forms. I think we did a really good job with the hardware.

|

|

|

Some online cialis people have superior complex regarding sexual performance, post-marital or relationship problems do affect your sexual health, depression is the issue that is haunting people today. The treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis can be long. cute-n-tiny.com viagra 100 mg This should not happen as it is not online cialis good taking the habit for granted. However, Sildenafil medication has been approved for the treatment of throat levitra uk cancer.

RFDB: Were there any canned projects that you were particularly fond of that you really wish had come to fruition?

Paul: Probably the most annoying is Super Battletoads on the Gameboy. Heard of it? No, nor has almost anyone else. It was the fourth one I’d written in the serious, was a spinoff from the arcade game of the same name, and was 100% finished and signed off by Test. Then it got cancelled shortly after I moved onto Donkey Kong Land because the arcade game had underperformed in market and Tradewest pulled the plug on the whole franchise. In 2015, during Rare Replay development, with long term members of Rare saying to me “don’t be silly, that game never existed”, we found it sitting on an old disc. A finished copy of the game. One of the engineers here happened to have a Gameboy emulator and we dragged the file into it and waited with bated breath. It ran! I couldn’t believe it, no one had seen this game in about 22 years, and I was the only person who recalled its existence at all. Then we needed to see exactly what was there and being a rock hard Battletoad game that no one had played in over 20 years it wasn’t going to be easy. However, I still had the sourcecode (which I had no way of compiling anymore but could look through anyway). I worked out an infinite lives cheat, applied it to the binary file by “poking” it and got one of our team to play through the whole thing in one go and record the video. It took a little over an hour (with infinite lives) but was all there. A 100% completed game. Apparently, no bugs were seen. Somewhere during the few years we worked on BT games, Kev and I worked on a street fighting game for SNES called Wrestlerage. Ultimately it suffered a similar problem to Beetlejuice in that we didn’t plan and communicate enough, and after a few months I went to Chris Stamper and asked if we could cancel and move on. Sometime after the KI franchise had died down, Tim asked me to look at it and see if there was a way forward, and after some work I pitched a design entitled “Killer Instinct: Redux”. However, we never got that off the ground as was too busy with other projects. It’s the nature of development that lots of ideas never get made, some are worked on for longer than others, some lose their way, some are randomised by external events etc., so there’s quite a long list of prototypes and ideas that staff here recall but were never released. In the case of Dream there were two different versions. The original one on SNES which looked awesome but was too late in the console life cycle, then the N64 version (which I worked on) that never got traction but spawned a character which we carried forward to become Banjo-Kazooie.

RFDB: Rare has one of the most diverse catalogs in the industry. What has it been like having the opportunity to work on so many different genres?

Paul: I do think it a shame these days that people can often work on one game for a long time and specialise in just one part of it. In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, you would spend 3-6 months writing a game, and then go on to do something else quite different in a similar timeframe. It was possible for an engineer to write three games in a single year, and have them really quite diverse such as a quiz show, then a racing game, then a beat ‘m up etc. It’s also not just the genres, but the diversity of what you would do on a single title. Initially you’d get the framework running with a bespoke engine (there was no middleware in those days). Then you’d start to implement gameplay, then you’d realise that the game will never fit on the cartridge so you design some data compression routines, then you’d spend days optimising the heck out of some code to get it to download everything to the video RAM during blanking fast enough, then you’d go back to gameplay, then someone would have an off-the-wall idea and some big random element would come out of nowhere and drive some other aspect of the work. The diversity was challenging, a deep learning curve, and ultimately very rewarding. Off the top of my head now I think I’ve been involved in titles that cover pretty much every genre you can think of; space shooters, racing, beat ‘m ups, platform, maze, puzzle, open world, god games etc, and it keeps things fresh.

RFDB: Recently, Banjo-Kazooie celebrated its 20th anniversary. What are some fond memories you have of working on the game?

Paul: Dream (on N64) had been difficult. Lots of activity but no actual gameplay materialising, and we were working long hours too with no result. Yet, within a week of our 4th restart meeting, we had something on the screen that resembled what ended up being the first level of Banjo Kazooie and for 16 months the team of about 15-16 people were absolutely blasting through it, seeing something fantastic appear, solving problems, having all of the diverse workload. It was actually really exciting because different people worked on different areas, and you would update your code to the latest build of the game and suddenly find a bunch of cool new things that had just gone it. The whole team went to E3 in Atlanta in either 1997 or 1998 to show the game off as it stood at that time, and I remember that we all had a great time, got an amazing response from people seeing it. Did some partying too. I think one of the things for me is that BK was a product of that group of people. There was a certain sense of humour that pervaded the group and that fed into lots of little touches in the game. The Jinjos, for instance, are a direct reference to one of our artists. Personally, I’m really proud of some of the technical solutions I implemented that either improved the game or allowed it to run at all within the hardware confines we had. Such as……

RFDB: So you were the mastermind behind Banjo’s infamous Stop N’ Swop. How did it come to be, why was it canned, and what was the overall plan for it?

Paul: …..One day Tim asked me if there was a way to transfer an unlock code from one game to another without using standard codes that could be “printed and typed in”. He wanted something that meant you physically had to have two cartridges to do the transfer (which might boost sales). I quickly came up with a technique based on residual data surviving a power outage on RAM, which I’d got from some effects we used to experience with home computers a decade or more earlier. I wrote a demo the same day, and that night Tim, Gregg Mayles and I sat in my room and went nuts swapping cartridges back and forth and examining the results. Someone subsequently christened it ”Stop ‘n Swap” and we found that a heavily error checked data packet could survive a journey of up to 24 seconds of total power loss. There are multiple reasons why this worked, but one of them is easily demonstrated if you disconnect a power brick for many gadgets from a wall socket and a little light on it carries on running for some time afterwards before fading out. We did a lot of testing on as much hardware as we had to ensure it was good. The feature was born. Assets went in, a plan was hatched to initially have 8 unlockables within BK that would connect to a notional sequel.

BK was written so that if you completed 8 tasks in the game then codes were dropped into RAM so that this (currently unnamed) sequel could recover and unlock features. However, we then wanted the sequel to send things back, so we got BK to look for incoming codes, and if they were found then they’d unlock access to a bunch of assets we’d baked into the game (seven Easter eggs and an ice key). However, BK was late (should have launched as Nintendo’s Christmas #1 in 1997, but was replaced by Diddy Kong Racing in the end), and Nintendo only found out what we were trying to do right at the end as we were trying to get a final build of the game to them for launch. They didn’t like what we had done, felt it was too risky, and told us to disable it. However, it was way too late to do anything about all the visual assets in the game, so they got left behind and a legend was born. Sorry about that. We did have a backup plan BTW, there were a series of long text codes we implemented that you could “type” in using the quiz board at the end of the game. Eventually some hackers found them I believe, but it meant that even if the feature hadn’t worked, we could have published the codes and allowed people to unlock things.

There’s one more aspect too; we weren’t just thinking about a sequel. We had a plan to connect six games together, each would pass codes to the next and if you completed the “full circle” by getting the last game to send codes back to the 1st (BK), then there was supposed to be an extra special bonus (which we never actually worked out). I don’t recall the exact order that the games needed to be played, but the six titles would have included Banjo Kazooie, Tooie, DK64 and Conker. My memory is hazy right now on the other two, but possibly Blast Corps and Perfect Dark , but can’t fully recall right now.

RFDB: What was the design process like for It’s Mr. Pants?

Paul: Ah, you used the word “process” which somewhat oversells anything we actually did as being “organised”. One day in 1999 Tim came to me with a sheet of paper with a few doodles on it and a set of rules for how some blocks could be placed and cleared in a grid. He was suggesting we could do a handheld puzzle game and asked if I’d look at it. Well, I dug up the sourcecode for Donkey Kong Land (which I’d finished four years earlier), disabled all the Donkey Kong bits and used the underlying framework to quickly build a prototype on. “Quickly” being the operative word. Later that evening (about 11 o’clock at night), I called Tim to say “I’ve done it”, to which his response was “done what?”. Anyway, I think he was gobsmacked that the base game was fully working in a few hours and we played it and realised that it did have something catchy about it. Unfortunately, that “write a game in a day” was a false dawn before what was about to happen.

David Wise had given us a bit of music from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite, and I suggested we call it Nutcracker, which Tim went with. However, as we kept working on it, it was clear that we needed a tangible hook for marketing. The development was not full-time. I had been doing production work on and off since DKL2 as well as other things, and sometimes the project would get focus again and off we went. At some point it moved from the GB Colour to the GB Advance, which meant writing everything from scratch again and also learning the new architecture. Someone decided that we should try to do it in a 3D or isometric view of the grid and I got this working. We also fully re-did all the art to brand it as Donkey Kong’s Coconut Crackers. Then in 2000 I ended up running some gameplay systems at E3 in LA to show the game off.

It was a funny show for Rare as almost everything on the Nintendo stand was ours, with one non-Rare title shown off behind curtains in a room round the back. DKCC was near the front-edge of the stand, and shared space with games that would end up becoming Kameo, Perfect Dark and about 3-4 others. So, there was a load of Rare people there showing off our wares, and lots of visitors would come and look at this odd block game with intrigue as it was nothing like anything else that we were known for or showing that week. However, afterwards, we didn’t like the 3D view (the GBA was not high enough resolution and everything looked blocky towards the back of the grid) and then in September 2002 we became part of Microsoft and the use of the DK franchise was now off-limits. It was at this point that serendipity kicked in and I found a new artist who had only just recently joined Rare had got a desk next to mine. His name is Ryan Stevenson (now Art Director on Sea of Thieves) and one day he turned to me and showed me a square picture that he’d doodled at home the previous night. “This is what your game should look like” were his words and it backfired (possibly) as I immediately agreed with him and within a few hours he was on the project fulltime. That 1st image of Mr Pants standing in front of his house, deliberately badly drawn went straight into the game as a gallery picture and Ryan just kept on going. We had a laugh to be honest, and when Robin Beanland began contributing with his infamous intro theme “Do, da-da, da-da, da-daaaa-da, do, do-do, do-dooooo” it just crystallised the silliness of it all.

Ryan and I kept riffing on things around several themes; adding lots of cultural/film references and putting pants on absolutely everything, including other pants where possible. Yes, there’s a monolith from a Stanley Kubrick film in there with a pair of pants on it. We didn’t stop. The main modes were simply about creating shapes, and we came up with the idea to attach animal and bird noises to them. There is no sense in this, which is why it fit the game perfectly. Tim came up with the idea of having pre-designed clearable puzzles, and the character of Helpo to, erm, “help”. However, if I’m honest, I never really liked the idea that we just told people how to do the puzzles, but it all ended up in the game anyway. There was a bonus mode called Max’s Mystical Muddle that I came up with based on a very simple progressive series of block challenges that was quite fiendishly difficult to do. It worked extremely well and exists in the game as an unlockable. The crayon snake was originally called the Pants Snake, but this was deemed a bit risqué so got changed, however I’ve no idea how it was any more dodgy than some of the other references and visual cues we put in.

RFDB: If there’s one thing you could change about any of the games you’ve worked on it, what would it be?

Paul: Every single project you come out of leaves you with a list of things you wanted to do. Without exception. I think Phil Collins once said something like “no album is ever finished, merely abandoned”, well it’s the same for games; there comes a time where you just have to stop working on them. However good and polished they look, the development team had a bunch of things left over that are looking for a home. Sometimes that home is in a direct sequel. When I wrote my first Battletoad game I wrote an engine from scratch and when I did the next one I upgraded the engine with some things that occurred to me during the production of the previous game. By the time I finished Super Battletoads I’d upgraded it three times already, and then had to do Donkey Kong Land that needed even more capability to download graphics data to the video RAM (which can only happen during blanking). So, I spent my first 3 weeks of that project heavily updating the engine again. On Its Mr Pants I was riffing on things right to the final build. Seriously, in the last few days before we shipped it I came up with the comedy titles in the credits, and managed to squeeze them in, whereas there were larger things I just didn’t have time for. Maybe we should do a sequel ?. To be more specific, I should have worked with Kev to design what we were doing for Wrestlerage better. I think some of the new ideas we put into DKR on Nintendo DS didn’t work as well as I’d have liked, such as blowing into the mic. However I really liked our idea for drawing a track outline on the touch-screen and then racing on that circuit.

RFDB: What advice could you give to others who are interested in pursuing a career in gaming as an engineer?

Paul: If you want to work in an established studio, bring something tangible to the table. Something that YOU have actually done. It can be with others, so long as there’s a part of it you can claim as yours. When I was interviewed to be an engineer for Rare in 1988 I was asked what formal qualifications I had and I refused to answer. This was for a job I really wanted. When they asked why, I pointed out that having a qualification in Geography (for instance) meant nothing for what I was applying for and I’d just brought an almost finished game that I’d designed and written for their evaluation. It was also being published by Codemasters. This sort of thing sets you aside from many other candidates who say they want to do something. We work in a creative industry so when I ask candidates what they do creatively in their spare time and the response is basically “nothing much” then they don’t normally go further. It was easier in the 1980’s when home computers were around because they offered a very simple way to “have a go at programming”. It got harder in the 90’s, but today there’s plenty of support for developing apps, and even publishing them if you wish. Come to us with something you’ve done, be able to discuss its merits and failures and have a sensible conversation with us about what you can do and what you could do better and we may keep on talking……

A huge thanks to Paul for taking the time from his busy schedule to conduct this interview!

[…] to RareFanDaBase, video game engineer, producer, and Rare veteran Paul Machacek has spoken about a long lost […]

[…] Speaking with the fansite RareFanDaBase this week, veteran Rare developer Paul Machacek said that the company had completed a port of Battletoads Arcade, a cabinet released in 1994, for Nintendo’s black-and-white Game Boy, but it was never released due to the poor sales of the arcade original. […]

[…] Speaking with the fansite RareFanDaBase this week, veteran Rare developer Paul Machacek said that the company had completed a port of Battletoads Arcade, a cabinet released in 1994, for Nintendo’s black-and-white Game Boy, but it was never released due to the poor sales of the arcade original. […]

[…] Speaking with the fansite RareFanDaBase this week, veteran Rare developer Paul Machacek said that the company had completed a port of Battletoads Arcade, a cabinet released in 1994, for Nintendo’s black-and-white Game Boy, but it was never released due to the poor sales of the arcade original. […]

[…] to RareFanDaBase, online game engineer, manufacturer, and Uncommon veteran Paul Machacek has spoken a few […]

[…] to RareFanDaBase, video game engineer, producer, and Rare veteran Paul Machacek has spoken about a long lost […]

[…] Fuente: RareFanDaBase […]

[…] If you’re interested in the full interview, you can see what else Machacek has to say about his experiences at Rare (there’s plenty more) here. […]

[…] unos días en una entrevista concedida por Paul Machacek (productor y diseñador de videojuegos en RARE) a la web RareFanDaBase, […]